In this post, we’ll analyze the Linux Driver of USB-Ethernet adapters, which are using AX88179/AX88178a chips.

Introduction

AX88179 and AX88178a is a chip from ASIX Electronics Corporation, which is a leading fabless semiconductor supplier with focus on networking, communication and connectivity applications, founded in May 1995 in Hsinchu Science Park, Taiwan.

AX88179 is a USB3.0 to 10/100/1000M Gigabit Ethernet Controller, and AX88178a is the one for USB2.0. Since there are still lots of devices which are using USB 2.0, they are usually integrated into one single adapter to provide backward-compatibility.

More information about the chips can be found on the offcial website of ASIX:

The one which I’m using is an adapter from Edimax, named Edimax EU-4306 Adaptateur USB Ethernet.

Everyone can buy it with a fair price - about 25 euros in France.

Driver Selection

The source code of the driver in current version kernel is located at drivers/net/usb/ax88179_178a.c.

Its first commit is on Mar 2, 2013. So, up to now, we should be able to use it without panic.

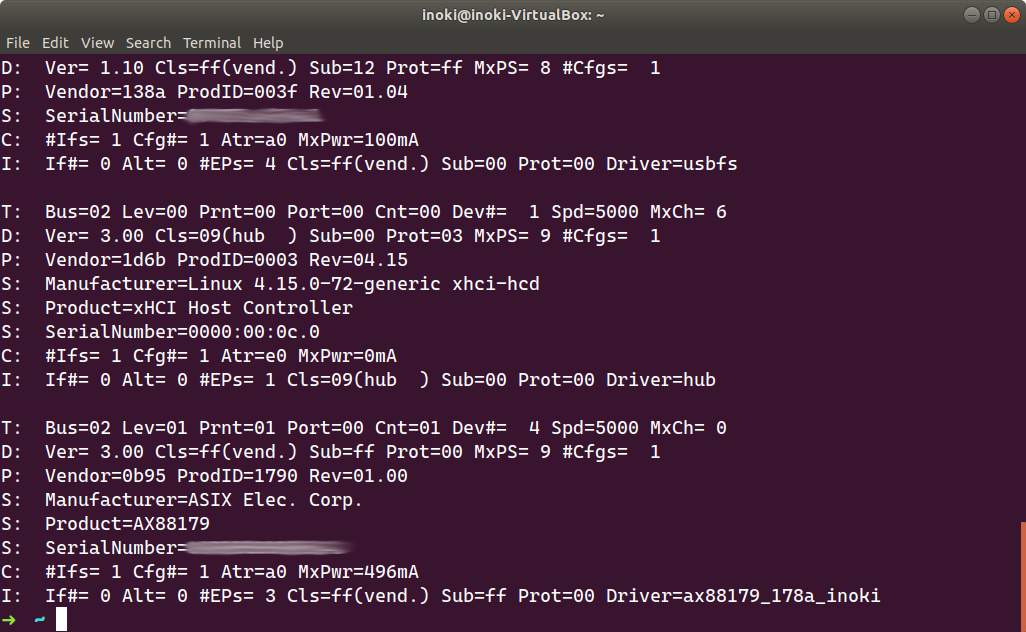

To validate that it can be rightly loaded in your system, just plug in. Use this command to find information of your device and the software assoiated with it:

1 | > usb-devices |

We can see at the last line, there is Driver=ax88179_178a, which means my device uses the right driver.

To associate a device and a usb driver, one important thing is the vendor ID and product ID, showing in the third line: Vendor=0b95 ProdID=1790.

So, if your device cannot be allocated with an appropriate driver, pleas check the vendor ID and product ID of it.

The ID table of compatible devices for AX88179/178a is defined as below:

1 | static const struct usb_device_id products[] = { |

Notice that USB_DEVICE is a macro defined in include/linux/usb.h, to quickly assign vendor ID and product ID. Meanwhile, make the mode be strictly matching, which means that only device has this vendor ID AND product ID will be allowed to use this driver.

1 |

|

More, products is a table of type struct usb_device_id, defined in include/linux/mod_devicetable.h. Since we’ve already included include/linux/usb.h\(<linux/usb.h>\), we do not need import it once more.

1 | struct usb_device_id { |

But, if yours is not one of them, it might be another device. This post will have limited usage to you.

Driver module registration

To make system be able to allocate the right driver, we need register the driver.

usb_driver structure

The structure to describe a driver for USB is defined in include/linux/usb.h:

1 | struct usb_driver { |

It’s a huge one, but we need not define all of them. What we need is just:

1 | static struct usb_driver ax88179_178a_driver = { |

.name

This is the name of driver, and it will be shown at the last line of the output of usb-devices.

I got the output above by changing the name to ax88179_178a_inoki.

struct usb_interface *intf

We can see that many of fields are pointers to functions with an argument of type struct usb_interface *intf.

It’s defined in include/linux/usb.h.

1 | struct usb_interface { |

With this parameter, we can distinguish which device is under operating. As well, it requires the caller pass a right reference 😃

.probe = usbnet_probe

The usbnet_probe is a function defined in include/linux/usb/usbnet.h.

1 | extern int usbnet_probe(struct usb_interface *, const struct usb_device_id *); |

When a device is plugged into the USB bus that matches the device ID that your driver registered with the USB core, the probe function is called, with the interface instance, and the device information.

.disconnect = usbnet_disconnect

Conversely, when the device is removed from the USB bus, the disconnect function is called with the device pointer.

For this callback and the callback which will be used in probing, the driver uses the standard USB net functions in include/linux/usb/usbnet.h.

1 | extern void usbnet_disconnect(struct usb_interface *); |

There are lots of standard functions defined in this header file. But we cannot expect the standard stuff can handle with all devices. So, in most case, we need write our own handlers for specific devices.

.suspend = ax88179_suspend

Called when the device is going to be suspended by the system either from system sleep or runtime suspend context.

This line can let the specific function suspend in the driver codebase be called.

.resume = ax88179_resume and .reset_resume = ax88179_resume

.resume will be called when the device is being resumed by the system.

.reset_resume will be called when the suspended device has been reset instead of being resumed.

Both two can let the specific function resume in the driver codebase be called.

Registration

Then, register the driver in the system.

1 | module_usb_driver(ax88179_178a_driver); |

It’s not a function, but a macro defined in include/linux/usb.h:

1 |

|

Then it will be expanded to a set of instructions in include/linux/device.h.

1 |

|

Such instructions can control the life cycle of a driver module. But we’ll not go deeper into the module functions, becaus they are out of scope.

Here, we come back to the module_usb_driver macro. Except __usb_driver is the specific driven instance, usb_register and usb_deregister could be also an interesting point in this post.

In fact, they are defined in include/linux/usb.h as well:

1 | /* |

The 2 functions will be called while module is being initialized or is being exited.

Core Functions

After the module life cycle management, here we need talk more about the actions of driver, while there are arriving packets.

Except vendor ID and product ID, there is also driver_info field which is set according to the different devices.

1 | { |

Driver Info

We can take a look at the 0x0b95, 0x1790(AX88179) and 0x0b95, 0x178(AX88178A). The driver info is an unsigned long pointer to the struct driver_info instance. Thus, Linux kernel can find the driver info instance when it needs.

The driver info structure is in fact a USB network driver info structure, defined in include/linux/usb/usbnet.h:

1 | struct driver_info { |

Just like the other huge structure, we will only use a small part of it.

AX88179 Driver Info

1 | static const struct driver_info ax88179_info = { |

AX88178a Driver Info

1 | static const struct driver_info ax88178a_info = { |

.flags

In flags, we might have several bitwise flag. This is created for some special feature of each device.

In these two devices, we have Ethernet device feature and ASIX specific device features.

1 |

Lifecycle-related sequence

System will call the function pointed by .bind to initialize device. The one pointed by .unbind will be called to do a cleanup in the system. To reset device, system will call .reset. To actively stop device, .stop will be invoked. Linux will also use .status to query the device satus. And .link_reset can be called for link reset handling purpose.

These functions are so long and so device-specific that we do not need to concentrate on them. The most important functionality is transmission of packets, which is implemented by .rx_fixup(for receiving), and .tx_fixup(for sending).

.rx_fixup

The function pointed by .rx_fixup works on doing frame stripping.

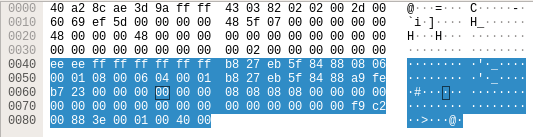

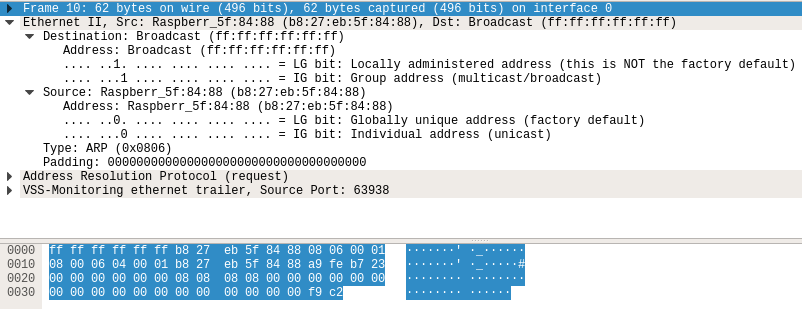

What’s frame stripping? These are two screenshots of an ARP network packet in USB traffic(above) and in Ethernet traffic(below), captured by Wireshark.

We can see that the highlighted part, from 0042 to 0079 in USB traffic, is exactly the same thing. So, what has RX fixup done is clear: it tries to extract the Ethernet packet from a USB frame.

Function Prototype

1 | static int ax88179_rx_fixup(struct usbnet *dev, struct sk_buff *skb); |

The function accepts two parameters, one is the deivce, the other is the data received.

The type struct sk_buff is defined in include/linux/skbuff.h, and is widely used in the network modules. It’s the abbreviation of socket buffer.

Implementation on mainline

In this chapter, we’ll take a look at every lines of this function on Linux Kernel mainline.

First, complying to C89, all of variables should be declared at the beginning of the scope block.

1 | struct sk_buff *ax_skb; |

ax_skb is a pointer which can point to a new socket buffer instance. pkt_cnt is the counter of packet, which counts how many packets are there in the packet.

rx_hdr can represent the header of the USB packet that we received, this variable is a 32 bits one, or 4 bytes or 4 octets. pkt_hdr is a pointer to unsigned 32 bits integer, literally it can point to the header of packet. hdr_off is an unsigned 16 bits integer, which records the offset of real header.

1 | /* This check is no longer done by usbnet */ |

In current version, the driver should check the length is compliable with the device or not. return 0 means that the packet isn’t handled correctly.

And then, it uses skb_trim to cut the last 4 bytes, reduce the length and calculate other fields in the structure.

1 | skb_trim(skb, skb->len - 4); |

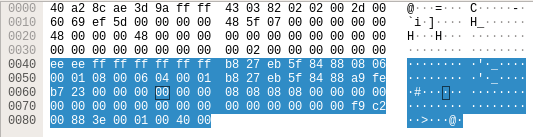

To know better how it works, we can take the previous packet to make an example:

With the trim function, the last 01 00 04 00 should be dropped.

1 | memcpy(&rx_hdr, skb_tail_pointer(skb), 4); |

But in fact, they are not totally dropper, the data is still their. The next step is rightly copying them into rx_hdr, with correspondant byte order. For example, my Linux is x86_64, so with little-endian. And the 01 00 is exactly 0x0001 in our brain. So, the number should be 00 40 00 01.

1 | pkt_cnt = (u16)rx_hdr; |

Then, with some magic, we can assign the packet counter pkt_cnt and the header offset hdr_off. With the humain readable representation 00 40 00 01, we could see there is one packet and the offset is 64 bytes (0x40 in decimal).

1 | pkt_hdr = (u32 *)(skb->data + hdr_off); |

We’ll have the header of the packet with pkt_hdr variable. In our case, it will point at a byte which has 0x40 offset from the beginning of the packet. We should notice that, the packet begins at 0x40, so, with the offset, it should point at 0x80, where there are 00 88 3e 00.

Then, we’ill attemp to iterately get all network packets in this single USB packet.

1 | while (pkt_cnt--) { |

As usual, do the initialization at first. We will extract the length of each packet to pkt_len.

1 | u16 pkt_len; |

Extract packet length.

1 | pkt_len = (*pkt_hdr >> 16) & 0x1fff; |

Here, we should have 00 3e 00 88 as the human readable order. So, the packet length should be 0x3e -> 62 bytes.

If we look at the USB-Net packet capture, we could know it’s correct!

1 | /* Check CRC or runt packet */ |

If AX_RXHDR_CRC_ERR or AX_RXHDR_DROP_ERR is set, just drop this packet because it’s not what we want. We only care the network packet.

1 |

The two flags are defined at the top of source code file. We can see in our packet, the 29th bit and the 31st bit are both 0. So, just ignore the code mentioned above. We continue.

1 | if (pkt_cnt == 0) { |

If we are handling the last packet, firstly we remove the first two bytes. They are two 0xee at the beginning. In this function, the length will also be reduced by 2. But it’s not the pkt_len, it’s the length field in the socket buffer instance which is reduced.

Then, we update the length to the right length of Network Packet and do some cleanup work. Then the stripped frame will be used by the system, as a network packet. Note: only the last packet will be “returned” by the origin socket buffer.

But if we take a look at the end of the network packet, there are serveral bytes which are not used by the protocol itself. This will lead an error, I’ll talk about it in the next post.

1 | ax_skb = skb_clone(skb, GFP_ATOMIC); |

Finally in the loop, we know that there are still several network packets in the USB packet.

So we try to clone the raw packet, regulate the boundary, and return it by usbnet_skb_return function.

If there are still packets to be handled, go on.

1 | } |

Otherwise, the loop ends.

1 | return 1; |

In the end, if we reach here, it means there are not any more the packets to be handled. So, it “reports” to the system that we’ve finished succefully.

.tx_fixup

After analysis of RX fixup, what TX fixup should do is obvious. It just wrapped the raw paquet into a USB frame, and send it to the device. The device will send it to the other side.

Function Prototype

1 | static struct sk_buff * |

The two first parameters have the same type, and the same usage as the two in RX fixup. The last one is a set of flags, but it’s not used in the implementation. So, we neglict it.

Implementation on mainline

1 | u32 tx_hdr1, tx_hdr2; |

Declarations and initializations of variables.

1 | if (((skb->len + 8) % frame_size) == 0) |

skb_headroom returns the number of bytes of free space at the head of an sk_buff.

So, this is a boundary check for adding more bytes.

1 | if ((skb_header_cloned(skb) || headroom < 0) && |

If our socket buffer is a clone or we have no more space to store stuff, we’ll fail to send.

1 | skb_push(skb, 4); |

Append the flag to the current end of packet.

1 | skb_push(skb, 4); |

Copy the length to the end of packet.

1 | return skb; |

Return the instance.

Conclusion

By analyzing this codebase, we should be able to know how a USB network device works.

In the next post, I’ll talk about the serious bug which is found in this driver.

See you!